|

----------

When the 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment emerges from the First Ypres massacres, 349 of its men, including List, lie dead. Only 611 remain unwounded. Hitler's own company is down from 250 men to 42. The "Kindermord" has the impact on Germany that the Somme has on Britain two years later.

The casualty bill will only increase. The List Regiment loses more than 100 percent of its paper strength, suffering 3,754 dead. Most battalions and regiments suffer the same losses. The Newfoundland Regiment, one of two Imperial outfits that fights at the Somme, also takes 100 percent casualties on the First Day of the Somme. When Newfoundland goes to war in 1939, its contribution will be an artillery battalion, not riflemen.

The new boss of the List Regiment is Lt. Col. Engelhardt, who goes up to the front with Hitler and another man to see the regiment in action against the London Scottish. The London Scottish spots the trio and open fire with machine-guns. Hitler and his pal hurl the CO into a ditch, saving Engelhardt's life. Without comment Engelhardt shakes hands with Hitler and his pal, and heads back to HQ to recommend them for Iron Crosses.

Next day, Engelhardt summons Hitler and four pals to give them the good news. After doing so, Engelhardt sends them out of the tent so he can reach for his dispatch form.

Just as they step out, a British shell tears into the headquarters tent, killing three officers and wounding Engelhardt. Hitler has had another narrow escape. But the medal recommendation doesn't go up the chain of command.

The war of movement is over, replaced by the stalemate of the trenches. Hitler finds it a liberating experience. He draws paintings of ruined villages in watercolors and actually paints a building, doing the officers' mess in a villa in bright blue. The new regimental adjutant, Lt. Wiedemann recommends Hitler for the Iron Cross 1st Class, but because Hitler is on regimental staff, this is whittled down to an Iron Cross 2nd Class.

When Hitler gets the hardware, it is "the happiest day of my life." He is promoted to lance corporal (Private First Class in the US Army), and gains the respect of his buddies, called Frontkampfer. He gains further loyalty by drawing cartoon sketches on postcards of the comical moments of war.

There is less loyalty from home. He gets no packages from the family in Linz, and has to buy extra food from the cooks. He is too proud to share his buddies' packages, and refuses a 10-mark Christmas gift from messhall funds. When the famous Christmas Truce of 1914 hits, the 16th Reserve Regiment is in the rear area. Later accounts of Hitler chatting with Tommies in No-Man's Land during the truce are false.

The List Regiment makes up its losses and goes back into action on January 22, 1915, marching into rainy, mud-sodden trenches, three days after the first German air raid on Britain. Hitler catches a small dog, teaches it tricks, and names it Fuchsl ("Little Fox"). The dog is more loyal to Hitler than people, never leaving his side.

From the mud, Hitler writes that the war will cleanse Germany from foreign influence at home and smash her enemies abroad. He tells his family that his home is no longer Austria but the 16th Regiment. On January 26, he writes the Jupps back in Munich: "Here we shall hang on until Hindenburg has softened Russia up. Then comes the day of retribution." The next day, British artillery salutes Kaiser Wilhelm's birthday with a heavy barrage.

Two days later, in the Argonne, a young German lieutenant named Erwin Rommel finds his platoon afraid to advance through French fire. He shouts, "Obey my orders instantly or I shoot you." The whole company crawls through the wire, and captures the enemy blockhouses, withstanding counterattacks until it is forced to withdraw. Rommel becomes the first officer of his regiment to gain the Iron Cross, First Class. Soon the regiment has a saying, "Where Rommel is, there is the front."

While the Frontkampfer talk of able leaders, women or food, Hitler talks only of reading, painting, art, or architecture. His buddies are impressed with his deep knowledge and his endless will. When not carrying messages, he studies maps of the terrain, so as to be a more efficient Meldeganger. Sometimes Hitler suddenly leaps up and dashes around, shouting that Germany has been betrayed, and the scum behind the lines are stealing victory.

His superiors are impressed by Hitler's determination and bravery as a messenger, dashing through shot and shell, carrying vital messages when telephone lines are blown out by artillery. Hitler volunteers to take the 3rd Battalion's critical "Urgent" messages, stamped

XXX, across the two-mile route, some of it underground, much of it under fire. A commanding officer commends Hitler for "exceptional pluck…and the reckless courage with which he tackled dangerous situations and the hazards of battle."

But the officers also regard Hitler as an unstable man, and do not recommend him for promotion. He finishes the war as a lance corporal. Amazingly, his failure to gain promotion does not bother him. He revels in being a common frontkampfer. He refuses to accept safer jobs.

He seems unbroken by the shelling and horror, reveling in it. When a buddy complains about smaller food rations, Hitler snarls that the French ate rats in the 1870 siege of Paris.

On September 25, 1915, poet Alan Seeger, serving with the French Foreign Legion in Champagne, writes home, "I expect to march right up the Aisne borne on an irresistible elan. It will be the greatest moment of my life." Edmond Genet, the great-great-grandson of Citizen Genet, Revolutionary France's representative in America, also has a revelation: seeing German POWs come stumbling along: "Some of them, mere boys of 16 to 20, were in a ghastly condition. Bleeding, clothing torn to shreds, wounded by ball, shell and bayonet, they were pitiable sights. I saw many who sobbed with their arms around a comrade's neck."

The British attack at Loos that day and the French also in Champagne. The British release 150 tons of chlorine gas from 5,243 cylinders in the general direction of Hitler's trenches. The wind goes wrong and the gas hits the British troops, leaving attackers unconscious and gasping. Piper Peter Laidlaw rallies his battalion and gains a Victoria Cross by playing "Scotland the Brave" on the parapet, amid the gas. The inspired Scots overrun the first two lines of German trenches. The "Roll of Honour" notices in The Times of London fill four columns.

That day, Hitler and a buddy go forward to find out why phone messages from the front have stopped. Surviving heavy barrage, Hitler returns to report that British shells have cut the phone lines, but another attack is coming. He seems to have a charmed life. Often he leaves a spot in a trench or a dugout only minutes before an enemy shell obliterates it. Supposedly he tells the other Frontkampfer, "You will hear much about me. Just wait until my time comes." However, this quote may be apocryphal.

Two days later, future British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, whose mother is from Indiana, goes into action with his regiment at Loos. He is wounded in the head and shot through the right hand, and evacuated, assuring his mother in spidery handwriting that he is "more frightened than hurt," but the battle is "rather awful." The wounding accounts for the limp handshake he will give for the rest of his life.

The rest of the British offensive goes no better. German machine-guns slaughter the British, leaving No-Man's Land covered with bodies and named, "Leichenfeld von Loos," the "Corpse-Field of Loos."

Christmas of 1915 is celebrated in the German way with caroling, amid drenching rain, continuous rolling British barrage, and parcels from home. German troops at Plugstreet Wood prop up a Christmas tree with candles on a parapet and the British shoot it down, obeying orders to prevent another Christmas Truce as in 1914.

Hitler lies on his cot in a trance, having received no parcels. He again refuses gifts from his buddies. But after the holidays end, he snaps out of his apathy.

In the summer of 1916, the 16th Regiment faces General Sir Douglas Haig's Big Push, the Battle of the Somme. On July 1st, the British launch an attack that consumes the lives of 60,000 of their own men on the first day. Despite enormous losses, the British offensive continues. New Zealander Bernard Freyberg, brave beyond belief, adds to his collection of wounds suffered, while earning a Victoria Cross, refusing to leave his battalion until their objective is secured.

Doubtless Hitler is unaware that Freyberg, a champion swimmer, oarsman, and boxer, is a dentist in civilian life, and now a hero in his native England and New Zealand, the country he moved to as a child with his father. At 6 feet 1½ inches, Freyberg has already gained the admiration of Winston Churchill and the British press as a living and scarred symbol of the British Empire's war effort. Freyberg has two good reasons to fight hard. Like another future Allied general, George S. Patton, Freyberg is cursed by a squeaky voice. More importantly, two of Freyberg's brothers, Oscar and Paul, have died in action, Oscar at Gallipoli, Paul in France.

Another Antipodean, Lt. Col. Iven Mackay, sees Germans refusing to abandon their dugouts until bayonet point. Even then, they are afraid to cross No-Man's Land because of the shelling. McKay will go on to lead the 6th Australian Division in the first Allied land victory of World War II.

Once again runner Hitler evades death. He watches his buddies from basic training die in the mud. For three months the Battle of the Somme rages. The Allies suffer 614,000 casualties, gaining very little ground.

Back in the trenches, Guards officer Harold Macmillan writes his mother, "The flies are again a terrible plague, and the stench from the dead bodies, which lie in heaps, are awful." Macmillan is wounded again on September 15, and lies for hours in No-Man's Land in a shell hole. He reads a pocket edition of Aeschylus's Prometheus, but no medics appear. Finally he struggles back to the battalion aid station. The bullet fragments in his pelvis are never removed, and Macmillan walks for the rest of his life with a shuffle.

Also killed in battle is Raymond Asquith, son of Britain's Prime Minister, shot through the chest as he leads his men forward. He dies on the stretcher taking him to a Dressing Station.

Years later, Hitler will discover that a British trench directly opposite him is held by a battalion of the King's Royal Rifle Corps. Its heroic adjutant: Anthony Eden, just out of Eton. At a dinner in Germany in 1936, Hitler sketches out the trench positions from memory and shows the British Foreign Secretary how the two were almost literally shooting at each other.

Eden's epiphany from the war is very different from Hitler's. Eden gains a Military Cross, but loses two brothers and a brother-in-law. The destruction convinces him that any future threats to world peace must be met with force, to prevent them from boiling into another world war.

On October 7, 1916, Ernie Shore and the Boston Red Sox defeat the Brooklyn Dodgers in the first game of the World Series at Fenway Park, 6-5. The Red Sox will go on to win their fourth World Series without loss, continuing their post-season dominance.

That day, Adolf Hitler's luck ends when he sits in a narrow tunnel leading to regimental HQ. A British shell explodes in the entrance, and Hitler takes a hit in the thigh. "It isn't so bad, Lieutenant, right? I can still stay with you, I mean, stay with the regiment, can't I?"

No. He gets evacuated on a hospital train to Beelitz Military Hospital in Berlin, seeing that city for the first time. The Beelitz beds are so clean, "We hardly dared to lie on them properly." Hitler gets a weekend pass to stroll the Reichhauptstadt's streets and is revolted to find Socialist and anti-war spokesmen in public meetings, denouncing short rations and agitating for peace.

Another one of Hitler's future enemies, Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov, is wounded in October, when a mine blasts him off his horse while on patrol in Rumania. Zhukov's hearing is damaged, but after a hospital spell in Kharkov, he is sent back into combat.

After two months, Hitler is also released from hospital. He is sent to a replacement depot, a fate familiar to American and British soldiers of both World Wars. Hitler's is in Munich. There he has ample time to brood on the rot of pacifism and Socialism infecting Berlin. The cause has to be the Jews. "Nearly every clerk was a Jew and nearly every Jew was a clerk. I was amazed at this plethora of warriors from the chosen people and could not help compare them with their rare representatives at the front." Ironically, thousands of German Jews are fighting at the front. 12,000 German Jews die, and some are earning Iron Crosses for their valor. The first Reichstag member to die in battle in World War I, for example, is Dr. Ludwig Haas, of Mannheim. These acts are performed despite Reich policies that ban Jews from certain regiments and military academies.

Hitler finds Munich changed. The replacements are conscripts, who do not respect the frontsoldaten. The British naval blockade has caused hunger, the endless war inflation. The conscripts mutter about Socialism and overthrowing the Kaiser and Generalstab.

In January 1917, Hitler is cleared for full duty and asks to return to the 16th Regiment. On five days after American newspapers publish the Zimmermann Telegram, Hitler's back with his outfit, and his little dog Fuchsl is among those happy to greet him. The company cook turns up trumps and gives the returning messenger a special meal of bread and jam and cake.

None of Hitler's pals comment on the revelation that Germany has offered to give Mexico the American states of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico in return for alliance against America. Nor is it likely they discuss how Germany has deported 700,000 able-bodied Belgian men as slave labor to German farms and factories, or that Austrian troops have executed 2,000 Serbs after an anti-Hapsburg uprising.

That evening, Hitler wanders the dugouts with a flashlight in hand, spitting rats on his bayonet, waking up his buddies. He stops only when one throws a boot at him.

The regiment's next destination is Arras, where the British are preparing a new offensive, which will be spearheaded by the Canadian Corps and the New Zealand Division.

Among Hitler's opponents this time is Lt. Col. Henry Crerar, a Canadian Scot from Hamilton, Ontario, an artilleryman. Another is Brig. Bernard Freyberg, who takes over the 173rd Brigade of the 58th British Infantry Division in April.

On April 9, Easter Monday, the Canadians attack, and both sides take heavy casualties. The Canadians gain considerable ground at Arras, moving behind a systematic rolling barrage designed by Brigade Major Alan Brooke. He will serve from 1941 to 1945 as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, gaining a Field Marshal's baton. In three-quarters of an hour, the British overrun the whole German front line. The Canadians gain the 250 acres of Vimy Ridge in a stunning victory and the land is given by France to Canada after the war as a memorial. Meanwhile, Hitler paints egg briquettes with calcium and place them in the regimental commander's garden, spelling out "Happy Easter 1917."

The next day, April 10, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin emerges from his famed "sealed train" in Petrograd, and calls for Bolshevik Revolution to overthrow Russia's Provisional Government.

A few months later, Major Freiherr von Tubeuf takes over the battered regiment, which has lost discipline as well as many men. Tubeuf finds command frustrating and criticizes his superiors. They ignore him. He relieves the tension by hunting in the rear area, and Hitler has to act as one of the beaters, flailing at the grass with a stick and shouting, to bring out rabbits. In all probability, this is a key source of Hitler's hatred of hunting, but he does not blame Tubeuf. Sixteen years later, he promotes Tubeuf to general.

After three years of war, Europe's social structure and manpower are ground into the mud of Flanders, and Hitler remains a lance corporal. Despite his gallantry, he doesn't do the small things that gain promotion: like polish his boots, click heels to salute, or wear his hat straight. Perhaps more importantly, the job of messenger is not authorized for a full corporal. Promotion would change his jobs - the regiment would lose its best runner.

In March 1917, the glittering prize of victory is handed briefly to the Germans as Russia's Czar Nicholas II abdicates. But the Kerensky Provisional Government promises to continue the war. The prize is handed back to the Allies in April, when the United States responds to years of insults and the arrogant German Zimmerman Telegram - which offers to divide up American states with Mexico like cookies - by declaring war on the Kaiser. In November, the prize is handed back to Germany, when Lenin and Leon Trotsky overthrow the Kerensky government in St. Petersburg with a few scuffles in the Winter Palace's halls. Later propaganda art shows Josef Stalin personally leading assaults or advising Lenin. The art, like most of Stalin's Russia, is a lie.

But these political gyrations have little impact on the battlefields. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig sends the British Army into its worst Calvary, the legendary Third Battle of Ypres. In July 1917, the British begin massive bombardments, using high explosives and poison gas. Hitler and his pals spend up to 24 hours straight in their stinking gas masks.

On July 31, the British attack, using a 3,000-gun barrage and enormous tanks. These rivet-hulled monsters, armed with naval guns and machine-guns, are partially the invention of Winston Churchill. They clank into action and the German defenses start to crumble. But the skies break loose and turn the Ypres battlefield into an enormous sea of mud. Tanks, horses, trucks, and men all sink into the quagmire. Nothing can move, least of all the advancing British. Captain Noel Chevasse, a British Army doctor and Victoria Cross recipient, is killed while bringing wounded men back. He dies two days later, and gains a posthumous bar to his Victoria Cross. Chevasse's brother is also killed in the battle.

Two days after the offensive starts, Royal Navy Cdr. Edwin Dunning takes his Sopwith Pup biplane off from an airfield at Scapa Flow and lands on the deck of the new aircraft carrier HMS Furious, something new in war. Five days later, Dunning does it again. But in making a third attempt, his plane slips over Furious's side and spirals into the sea, killing Dunning. But a precedent for warfare has been set.

In Flanders, Haig's officers are stunned by their own blundering. The maps don't reveal the mud. But British shellfire has destroyed Flanders' drainage systems. A British staff officer, Launcelot Kiggell, visiting the muck for the first time, gasps, "Did we really send men to fight in that?"

"It's worse further up," his escort snarls.

Hitler is not present for any of these blunderings. The 16th Regiment gets yanked out of the line in August, shot out. It moves down to Alsace for a rest. A railway official offers Hitler 200 Marks for his terrier, Fuchsl. Hitler won't sell the dog for 200,000 Marks. But it disappears when the regiment hops off the train in Alsace, and Hitler has no time to find his dog.

At the same time, a rear-area soldier goes through Hitler's knapsack and steals a leather case containing Hitler's artwork and supplies. Hitler is enraged by the thieving and profiteering in the rear area.

After an 18-day furlough, Hitler returns to the front to see little action for the rest of the year. The Alsatian front is a quiet one, with French and German mountain units periodically slugging it out for hills named Hartmanns Villerkopf, but otherwise little action. Hitler reads history and the philosopher Schopenhauer again and again. "War forces one to think deeply about human nature," Hitler tells his lawyer Hans Frank years later. "Four years of war are equivalent to 30 years university training in regard to life's problems."

But while the fighting has died down, the war gets worse. Shortages are everywhere. The List Regiment has to eat cats and dogs. Hitler prefers cat meat, and occasional toast and marmelade.

The 16th is lucky. Back in the Reich, civilians are eating dogs and cats ("roof rabbits"), bread made of sawdust, and potato peelings. One-pot meals once a day are not enough. There are also shortages of coal, oil, chocolate, and cigarettes. German imports are strangled by the British blockade. Butter and fat imports drop from 175,000 tons in 1916 to 95,000, fish from 420,000 to 120,000, meat from 120,000 to 45,000. German census statisticians attributed 121,114 deaths in 1916 to the blockade and 259,627 deaths the following year. Food riots break out in many German cities in 1916. Strikes follow in Berlin, Magdeburg, Hamburg, and Leipzig in 1917, against reductions in the bread ration.

But while workers starve, the aristocracy eats well, dining on black-market caviar. Germany, a nominal democracy, is now a military dictatorship under the Quartermaster General, bull-headed and anti-Semitic General Erich von Ludendorff, whose ruthless methods foreshadow the end of the next great European war.

These excesses inflame the starving German workers. On January 28, 1918, while Canadian Lt. Col. John McCrae - author of "In Flanders Fields" - dies in a military hospital in Belgium and Leon Trotsky forms the Red Army to bar Lenin's opponents from the Constituent Assembly in Petrograd, strikes explode throughout the Reich.

The direct cause: the announcement of "meatless weeks." The deeper cause: Bolshevik propaganda and the successful Russian revolution. Workers march out of factories, demanding peace, more food, no martial law, and democracy. The protests in Munich and Nuremberg are small and peaceful, but 400,000 march in Berlin. A week of protests ends in arrests and roundups, but the frontsoldaten read all about it in letters and Bolshevik pamphlets.

The frontkampfer are as worn out by war and privation as their families back home, but all feel betrayed. Hitler is enraged by "slackers" and "Reds." He snarls, "What was the army fighting for if the homeland itself no longer wanted victory? For whom the immense sacrifices and privations? The soldier is expected to fight for victory and the homeland goes on strike against it!"

Nevertheless, on March 3, the Germans bully the new Soviet regime into signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This treaty, an exercise in power and humiliation, deprives Russia of vast tracts of her land and grain. It also gives Hindenburg and Ludendorff 3,000 guns and a million fresh men to hurl at the West. Hitler is exhilarated by the treaty, as are many German soldiers.

For months the Germans have reorganized their armies, stripping divisions of men, to create the new Stosstruppen Divisions, trained in new infiltration tactics designed to break the trench stalemate. The Stoss Divisions are equipped with portable mortars and poison gas, but more importantly, trained in stealth, mobility, and shock warfare - precursors to Hitler's blitzkriegs 20 years later.

Hitler's 6th Bavarian Reserve Division is one of many trained as a Stoss outfit. On March 21, 1918, the List Regiment goes over the top at the Somme in the Kaiser's Battle, driving the British across the old battlefield. The first weight of 6,000 German heavy guns hits a British headquarters just as the Minister of Munitions, Winston Churchill, is visiting the officers. Churchill is only just able to leave the battlefield before the Germans overrun it.

The offensive blasts open the British 3rd and 5th Armies. Then it hurls the French across the Aisne. Soon the Germans are only 50 miles from Paris. The Germans fail to take Amiens, so they attack on the Lys River, drenching Portuguese and British defenders with poison gas. More than 8,000 men are wounded.

Haig, facing disaster, proves as stubborn in defense as he is in attack. He issues a Special Order of the Day on April 11: "With our back to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight to the end." The troops believe it, too, and even more so when the first American units move up to stop the Germans at Meteren and Kemmel on the old Ypres battlefields. Amiens holds, but the Germans turn south, heading for the Marne and Paris. They drive a 40-mile-wide, 15-mile-deep wedge into Allied lines, killing, among others, Major Bertram Cartland, father of novelist Barbara Cartland. She will lose two brothers in the 1940 retreat to Dunkirk.

On April 20, Hitler celebrates his 19th birthday by fighting in the battles. Next day, Manfred von Richtofen, the "Red Baron," is shot down. His cousin Wolfram von Richtofen will lead Luftwaffe air fleets in Russia and Italy in World War II. A former cavalry lieutenant and fighter ace named Hermann Goering is named to command Richtofen's old squadron, whose officers include another lieutenant named Ernst Udet. Goering shows ample determination in air battle, earning a Pour le Merite on June 2.

On May 9, Exterminator wins the Kentucky Derby, and Hitler gets a regimental diploma for outstanding bravery. His valor is not enough: despite successes, the Allies are not collapsing. The Germans attack on May 27, backed by 4,000 Krupp guns. Gas and shrapnel overwhelm the British and the German Siegessturm drives ahead 12 miles to the Marne through five French defense lines, to a point 37 miles from the Eiffel Tower.

At Chateau-Thierry the Germans face a rolling field of summer wheat, scarlet poppies, and a gigantic forest. The Germans also face a freshly-arrived force that has just marched through clouds of dust and refugees - the 5th and 6th Regiments of the United States Marine Corps. A French refugee shouts, "La guerre est fini!" A Marine shouts back, "Pas fini!" - which gives the sector its name for the five-day battle. There, at the Belleau Wood, the Marines suffer 6,000 casualties, gain 100 Distinguished Service Crosses, and stop the Germans cold. Many of the young Marines who emerge from the wooded cauldron will lead another generation of Leathernecks in even denser forests and more vicious battles in another hemisphere, 20 years later.

At Cantigny, the US 1st Infantry Division stops the German advance. A young American Army officer, Clarence Huebner, sees German troops fire off their ammunition until they run out, then shout "Kamerad." The angry Americans ignore the plea, and shoot the Germans. Twenty years later, Huebner will lead the same US 1st Infantry Division into France and Germany.

On June 2, the United States sets a shipbuilding record, launching the Wickes-class "four-pipe" destroyer USS Ward, (DD-139), in 17½ days. At 1,000 tons and armed with 5-inch guns and torpedoes, she is the cutting edge in destroyer design for 1918. Twenty years later, she will be obsolete. But on December 7, 1941, she will make history again: firing the first shots at Pearl Harbor, and sounding a tocsin that is ignored.

The Germans continue to attack, using the Krupp Pariskanone hurling 200-lb. shells 77 miles into Paris, killing Parisians in 20 weeks of shelling. One 35,000-mark shells blasts open the roof of Saint-Gervais-l'Eglise during Mass, killing 91 civilian worshippers and wounding 1000. This incident makes Germany more hated than ever.

German morale is low from casualties, exhaustion, and hunger. Now they face the American army, which seems to spring an endless array of huge, well-equipped, well-fed, aggressive soldiers from everywhere at once.

Hitler does not see them. But in June, while carrying messages, he sees what appears to be a French helmet in a trench. Hitler whips out his pistol (messengers have traded in rifles for pistols) and shouts orders as if he is leading a company of German soldiers. Four poilus surrender. Hitler takes his haul back to Von Tubeuf, who is impressed.

The colonel later says, "There was no circumstance or situation that would have prevented him from volunteering for the most difficult, arduous and dangerous tasks and he was always ready to sacrifice life and tranquility for his Fatherland and for others."

With the German offensive effort nearly spent, the Allies start counterattacking, using American and British troops as well as the new tanks. The Spanish Influenza sweeps through the front lines and rear areas, killing millions on both sides, but hitting the hungry German home front the hardest.

Princess Blucher, the English wife of a German nobleman, writes that she has little to eat but smoked meat and dried peas and beans, "but in the towns they are considerably worse off. The potatoes have come to a premature end, and in Berlin the population have now a portion of 1 lb. per head a week, and even these are bad. The cold winds of this wintry June have retarded the growth of all vegetables, and there is almost nothing to be had. We are all waiting hungrily for the harvest and the prospect of at least more bread and flour."

The Germans make one more try on Bastille Day, but the Chief of Staff of the US 42nd Infantry Division personally leads a determined defense. His name: Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur. He later gains his fourth Silver Star when he personally leads a reconnaissance patrol into German lines.

Next day, Quentin Roosevelt, son of President Theodore Roosevelt, is killed when his plane is shot down. Quentin's brother Theodore Roosevelt Jr., serving in the infantry, will go on to become a fierce foe of the Germans in World War II. By July 18, the German threat to Paris is over. By July 22, even the arrogant Kaiser Wilhelm II is depressed.

On August 4, the French recapture Soissons, taking 35,000 POWs and 700 guns. The same day, U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, visiting the war, finally reaches the front, at the village of Mareuil-en-Dole. His "sensitive naval nose" tells him he has reached the front, he writes later to his wife Eleanor and mistress Lucy Rutherford. The smell is that of dead horses, still awaiting a veterinary and graves registration outfit to handle the clean-up.

Roosevelt finds the Americans have just take the village. Corpses of Germans lie in a heap, also awaiting the graves registration team. FDR also finds a US artillery battery hard at work, shelling the German lines four miles away. The gunners let Roosevelt pull the lanyard on a shell aimed at a railway junction at Bazoches, eight miles to the north. A spotter plane reports the shell hits its target. FDR writes, "I will never know how many, if any, Huns, I killed."

Later that day, Roosevelt sees an American regiment coming out of the line, and he is appalled by the bleeding wounded and the men coughing out their gassed lungs.

But as the Germans retreat that day, the List Regiment finds time to award Hitler the Iron Cross, 1st Class, for "personal bravery and general merit." It is a high decoration for a lance corporal, and he wears the medal for the rest of his life. The man who puts forward the paperwork for the hardware is the regimental adjutant, Captain Hugo Guttman, a Jew.

When Hitler comes to power, Guttman will save himself from his old corporal's wrath by immigrating to Canada.

The Iron Cross is not Hitler's sole award: he also earns the Military Cross, 3rd Class, with Swords; the Service Medal, 3rd Class, and Germany's version of the Purple Heart, the Verwundeterabrechnen (the Medal for Wounded). It is a typical array of awards for a Frontkampfer.

Four days later, the British launch their massive armored assault at Amiens, under Australian General Sir John Henry Monash, a Jew. It is the first mechanized assault in history.

Relying on British tanks, American engineers, and British, Canadian, and Australian ferocity, the British gain 12 kilometers. The Australians capture nearly 8,000 men and 173 guns, losing less than 3,000 men. The Canadians capture 5,000 Germans, and also about 3,000 men. Stunned Germans throw down their rifles as scores of tanks come charging at them in waves. The only Germans who seem to fight hard are the men of the Richtofen Squadron, under their boss, Lt. Hermann Goering.

All behind the German lines, the effect of defeat, hunger, war-weariness, and Bolshevik propaganda impacts on the Frontkampfer. Army censors report letters going home that read, "The war will end when the great capitalists have killed us all." Another reads: "You at home must strike, but make no mistake about it, and raise revolution, then peace will come."

Fresh troops coming into the line find their buddies retreating in disorder, shouting, "What do you war-prolongers want? If the enemy were on the Rhine, the war would end!" Others yell to replacements, "Blackleg! Scab!" One troop train in Nuremberg bears the inscription "Slaughter cattle for Wilhelm and Sons" scrawled on the side.

Even the Kaiser himself is gloomy, remarking at his headquarters in Spa, Belgium, that "We have reached our limit."

The 263rd Reserve Regiment comes up to relieve the 1st Reserve Division, which is pouring back. The men of the 1st shout, "We thought we had set the thing going, now you asses are corking up the whole again." The Alpine Corps finds complete confusion: "Individuals and all ranks in large parties are wandering wildly about, but soon for the most part finding their way to the rear…only here and there were a few isolated batteries in soldierly array, ready to support the advancing troops."

Col. General Erich von Ludendorff, the First Quartermaster-General of the Army and its guiding brain, calls August 8 "the black day of the German army," and breaks the bad news to the Kaiser at the Hotel Britannique in Spa on August 11. "The German Army is no longer a perfect instrument," he says. That is an astounding statement - what army in the world is a perfect instrument, even in the best of times?

But Ludendorff, who has many abilities, lacks firmness and resilience in crisis. Ludendorff says that German strategy must be "to paralyze the enemy's war-will with a policy of strategic defense." His pessimism infects the entire German high command and its allies. Austria-Hungary says it cannot fight past December.

The Kaiser says, "It is strange that our men cannot get used to tanks." Twenty years later, they will. Then the All-Highest orders his foreign ministry to begin peace negotiations, but Hindenburg protests: the German army still holds much enemy territory. Ludendorff's answer is a harsher one, with longer impact: he calls for tighter discipline at home and "more vigorous conscription of the young Jews, hitherto left pretty much alone."

With that done, the Kaiser returns to the Imperial private castle at Wilhelmshohe to view art galleries and do pencil sketches.

Hitler's regiment fights and retreats, fights and retreats. Machine-gunners, their Maxims scalding-hot, hold off the Allied advance while the rest of the army flees.

Lt. Alfred Duff-Cooper, a future leading British politician, aged 18, on his first battle on August 20, fires a single shot down into a railway cutting and 19 Germans emerge from hiding to surrender. "If they had rushed me they would have been perfectly safe, for I can never hit a haystack with a revolver and my own men were 80 yards away. However they came back with me like lambs, I crawling most of the way to avoid fire from the other side of the railway. Two of them who were Red Cross men proceeded to bind up my wounded." The French 4th Army also captures 4,000 Frontkampfer that day.

Two days later, Duff-Cooper attacks again, after a 4 a.m. barrage. "I felt wild with excitement and glory and knew no fear. When we reached our objective, the enemy trench, I could hardly believe it; so quickly had the time passed it seemed like one moment. We found a lot of German dead there. The living surrendered."

The German Empire is cracking, but not Hitler. He is enraged by the impending collapse, and shouts "in a terrible voice that the pacifists and shirkers were losing the war." When a new NCO suggests that further fighting is stupid, Hitler flies into the sergeant with his fists, beating him. After that, all the new recruits "despised (Hitler) but we old comrades liked him more than ever," according to Hitler's pal Schmidt.

Hitler is furious with the growing treachery, and gets to see it up close. In September the 16th Regiment is pulled out of the line, and Hitler gets a two-week furlough to Berlin and the family farm in Spital. In Berlin, he is stunned to find Socialist speakers on the streets, hunger, poverty, and defeatism in the air. Princess Blucher writes, "The whole situation is so perilous at the moment that everyone feels something momentous must be going to take place. Wounded men refuse to consent to operations which might heal an injured limb, on the ground that they would then be sent back to the front and they have no intention of going there."

The Kaiser tries to boost morale at the Krupp works at Essen, inspecting the mighty factory on September 9. Die Konzernherr, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach writes up a tight timetable that calls for Seine Majesitat to inspect the Gusstahlfabrik's main machine shops. But the Kaiser whips through the inspection quickly while the Kaiserin passes out decorations to Krupp executives.

After a 20-minute lunch, the All-Highest tells Gustav that he really wants to address the ordinary Kruppianer. In his dress uniform, with curled hair, clutching his walking stick, S.M. stalks through gate no. 28, and points at a coal dump. The Kaiser will speak from there.

Krupp warns that one slip on that coal pile and the All-Highest's dress uniform and public image will be beyond cleaning and repair. Gustav points to a huge shed, and 1,500 men are rounded up from the foundry in their paper shirts and wooden clogs to hear their Kaiser.

The All-Highest tells them that anyone spreading false rumors or circulating anti-war leaflets will be hanged. He adds that both Kruppianer and Kaiser are working for Germany, "I on my throne and you on your anvil," and the exhausted workers merely react with grim muttering. Clearly they aren't happy.

The unnerved Kaiser wraps up his speech, gesturing with his withered left arm, saying, "Be strong as steel, and the solidity of the German people, welded into a single steel block, shall show the foe its strength. Those among you who have been moved by this appeal, those whose hearts are in the right place and who will keep the faith, let them stand up and promise me in the name of all the workmen of Germany: We shall fight and hold out to the man, so help us God! Let those who will do this answer me by saying Yes!"

But no "Jawohls" rise up in the shed. Finally one man yells, "When will we have peace?" Another shouts, "Hunger!"

An agitated Kaiser reacts his ending: "I thank you. With this Yes I will go to Field Marshal Hindenburg. Every doubt must be removed from my heart and mind. God help us. Amen. And now, men, farewell!"

The All-Highest speeds off in his limousine, leaving in his wake disillusioned workers. The rumors that the angry workers killed the Kaiser spreads, followed by the truth: that S.M. lied to his people, and like a wave spreading in a pool, the shock of truth spreads throughout the Reich.

Back to the front, Lt. Col. George S. Patton Jr. leads his tanks forward in an attack, heading 200,000 Americans into the assault on St. Mihiel. Douglas MacArthur enters the town of Essey to find "A German officer's horse saddled and equipped standing in a barn, a battery of guns complete in every detail, and the entire instrumentation and music of a regimental band."

MacArthur can see Metz through his binoculars and asks the US 1st Army's Chief of Operations, Col. George C. Marshall, for permission to advance. Marshall turns MacArthur down, concerned about logistics and running into other advancing Allied troops. While MacArthur sees the spires of Metz, Marshall sees that Patton's tanks have had to wait 32 hours for gasoline trucks to cover nine miles, and American men who lack food and dry socks. The U.S. Army has ample determination, ferocity, and drive. But it lacks efficient quartermasters, logisticians, engineers, and transportation men. Marshall, who is trying to move 428,000 men to the front and keep them fed, takes grim note of these weaknesses for the future. He also has to feed 90,000 horses and mules, and notes the difficulty of supplying such a large mass of transport with fodder. A replacement will be needed.

But MacArthur regards Marshall's refusal as a personal affront, beginning a feud between the two generals that will last through the next World War.

At the front, the Americans advance through red, gold, and copper trees in the foggy Argonne, where runners, officers, and a famous battalion get lost. One patrol disappears, Indian file, into a haze, and neither the men nor their bodies are ever found.

Hitler is also back in action, once again at Ypres. But the edifice is cracking. On September 25, Bulgaria asks for an armistice, cutting off Turkey. On the 28th, Ludendorff struggles to restore order from the situation, as defeat looms everywhere. He has no reserves, treachery is everywhere, and he can control nothing. The Kaiser is weak, the Navy incompetent, the Army overloaded. Hysteria grips the exhausted quartermaster-general of the Army, and his voice becomes hoarse, face red, then pale. At 4 p.m., foam bursts from his mouth, and Ludendorff crashes to the floor with a nervous breakdown.

When he recovers, Ludendorff tells Hindenburg Germany must sue for peace. The position will only grow worse. Hindenburg tells Ludendorff he was going to suggest the same thing to the Kaiser. "The Field-Marshal and I parted with a firm handshake, like men who have buried their dearest hopes, and who are resolved to hold together in the hardest hours of human life as they have held together in success."

That same day, New Yorkers begin a small revolution in public transportation with the opening of the Grand Central-Times Square subway shuttle. The Interborough Rapid Transit's directors promise that the shuttle will be a "temporary measure."

On September 29, Capt. Harry Truman's American artillery fires on three German batteries, destroying one and forcing the other two to flee. Truman writes, "The regimental colonel threatened me with a court-martial for firing out of the 35th Division sector! But I saved some men in the 28th Division on our left and they were grateful in 1948!"

The same day, the Kaiser returns to Spa. At the Chateau de la Fraineuse, the Kaiser's residence, the Generalstab delivers its bleak report to the All-Highest, and agrees to submit German acceptance of the Allies' Fourteen Points of peace. Admiral Von Hintze, the Foreign Minister, tells the Kaiser that the domestic situation requires a change. Power must be given to the Reichstag, and Chancellor Hertzling, a mere puppet, must go. What is needed is a "revolution from above."

Wilhelm II takes this shocker with unusual calm. Normally a man of angry rages and violent mood swings, often out of touch with reality, the Kaiser takes his decisions calmly and quickly. He signs "the most difficult document of his career," a proclamation of parliamentary government. By evening, though, at the dinner table, the normally pompous All-Highest seems broken and aged.

Now comes a search for a new Chancellor. Ludendorff bursts in on the All-Highest at dinner, and shouts, "Is the new Government formed?"

The Kaiser answers wearily, "I cannot work miracles."

The donkey's tail is placed on the Kaiser's second cousin, the liberal Prince Max of Baden. He is heir to the Baden ducal throne, an army major-general, and nobody's fool. He will only take office if Seine Majestat agrees that the Reichstag will have the power to declare war and make peace, and the Kaiser yield his control of the armed forces. The Kaiser agrees, ending Wilhelm's divine right.

The Supreme Command tells Prince Max to request an immediate armistice. Prince Max retorts that if the Army is losing, it should simply hoist the white flag. The Generalstab refuses to be the instrument of surrender. They insist they haven't lost the war. Prince Max has to do it. Prince Max is stunned. He hasn't been on the job long enough to print business cards, let alone sign an armistice to end a World War. He needs time to organize Germany's proposals. Hindenburg is not one of Germany's quicker minds. He goes to the phone to call Ludendorff in Spa.

Meanwhile, Major von dem Bussche, the Army's liaison to the Reichstag, briefs the party leaders on the military situation. Bussche is blunt: "we can carry on the war for a substantial further period, we can cause the enemy heavy loss, we can lay waste his country as we retreat, but we cannot win the war." He warns that the political leader must lose no time: "Every 24 hours that pass may make our position worse, and give the enemy a clearer view of our present weakness."

The listeners are stunned. Friedrich Ebert, Secretary of the Social Democrat Party, who will be Weimar's first Chancellor, goes white as death and is unable to speak. National Liberal leader Gustav Stresemann looks as though he has been struck by another man. Conservative wheelhorse Ernst von Heydebrand shouts, "We have been lied to and betrayed," sounding the chord for the future. Prussian Minister von Waldow staggers to his feat, saying, "There's only one thing to do now - to put a bullet in one's head."

However, the extreme left is delighted, seeing their opportunity to topple over the entire Hohenzollern dynasty.

On October 3, Prince Max accepts the Chancellery, saying, "I thought I should have arrived five minutes before the hour, but I arrived five minutes after it." He forms the first German government whose members are responsible to its elected parliament.

Then he gets Ludendorff's answer on the Armistice, which is signed by Hindenburg. Ludendorff is still in the despair of his breakdown. He says the Army cannot make good the losses of the last few weeks. Prince Max is stunned.

He'd be more stunned to know that the Generalstab is in chaos, shouting at each other in Spa, an unthinkable event for the heirs to Blucher and Gneisenau. Hindenburg has talked of "fighting to the last man" if the Allies insist on humiliating terms. The Finance Minister points out that such a deed is possible for a single battalion, not for a nation of 65 million.

Prince Max sends the telegram to American President Woodrow Wilson on October 4. The telegram asks merely for an Armistice, based on the famous Fourteen Points, which owe their name to a scornful editorial in Germany's Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung. No pre-conditions. Germany would still hold the Alsace-Lorraine and Poland. Austria-Hungary sends an identical one the same day. And a German U-boat sinks a Japanese liner, the Hiramo Maru, off the Irish coast, killing 292 people.

On October 7, Poland declares its independence in Warsaw, and Prince Max has a new problem, how to hold an area that has gone into revolt. On October 11, Wilson gives his answer: the pre-requisite for an armistice is German withdrawal from France and Belgium. And the Allies ask if the German government represents the Kaiser or the German people.

Prince Max answers the note by saying he represents the German people, has the power, and is willing to evacuate occupied territory.

A week later, while the Allies recognize Thomas Masaryk's Czech National Council, the British attack the List Regiment at Wervik, near Ypres, on October 14. Hitler is in the line when a British mustard gas shell explodes. He slaps a mask on his head and keeps it there through the shelling, even though the air becomes dense and stale. A suffocated recruit pulls off his mask to breathe and instead goes into agony from the mustard. But some of the gas gets into Hitler's lungs, leaving him temporarily blinded.

Medics form the half-blinded men into a line, clutching coattails, and they shuffle back to the rear, and then onto a train to Pasewalk Military Hospital in Pomerania, eyes swollen, faces puffed up. Hitler's war is over.

But World War I still has a month to run. Advancing French troops find that the Germans have left six days of food in Lille for the citizens. Advancing British troops find the Germans have smashed everything in Douai, even furniture, crockery, pictures on walls, and ripped the reeds out of the cathedral's pipe organ. At least the booby traps are sprung, as the retreating Germans now fear more international complaints about their inhuman warfare.

While Hitler shuffles back through a fog of poison gas and shellfire on October 14, Wilson sends a second note to Germany, ordering the Reich to abandon the U-boat war and its "arbitrary power" that has governed Germany for years.

The Kaiser correctly interprets this as an order to end the Hohenzollern monarchy, and ensure that the German government that makes peace is a democracy. The Kaiser has to abdicate. Everyone outside of the Generalhauptquartier at the Hotel Britannique in Spa knows this. Princess Blucher writes, "Why had he let things go so far? Why has he not already abdicated instead of waiting until he is forced to do so? Every child in the street is saying, 'The Kaiser must go.' He absolutely seems to cling to his shadow of a throne."

But S.M. won't go. Ludendorff, having recovered his nerve, says that the situation is not so bad, and Germany should fight on. An Allied breakthrough is "unlikely." He plans a 1919 counteroffensive, relying on captured Russian wheatfields and surrendered Russian gold to feed the war.

Ludendorff and the Kaiser are out of touch with reality. In Berlin and other cities, public transport has broken down. Shops have nothing to sell. There is no rubber, paper, cotton, leather, textiles, or clothing. "If one looks at the women," a medical officer writes, "Worn away to skin and bone, and with seamed and careworn faces, one knows where the portion of food rations assigned to them ahs really gone." On October 15, Spanish Influenza kills 1,700 Berliners. Socialist leader Philipp Scheidemann, a former printer, says, "Better a terrible end than terror without end."

Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, boss of an Army Group, notes his troops' wretched condition. He writes that the men are "depressed in body and mind." His troops are surrendering in hordes, and other hordes of deserters plunder towns behind the lines. There is no fuel, no prepared lines, no reserves. He doesn't expect to hold out past December, and writes: "We must obtain peace before the enemy breaks into Germany."

Indeed, most of the German army is now a disorderly mob of angry refugees, feeling themselves betrayed by their Generalstab. The Allies are being held up by their own logistical problems and determined machine-gunners, who keep their Krupp barrels hot. Sgt. Alexander Woolcott writes in The Stars and Stripes that the German Army resembles an escaping man who "twitches a chair down behind him for his pursuer to stumble over."

Prince Max summons the Generalstab on October 17 to draft a reply: Hindenburg, Ludendorff, and von dem Bussche. Ludendorff calls for a levee en masse, saying Germany still has 35 and a half divisions. But he warns that those coming from the Eastern Front are "exposed from the corruption of Jew traders in the East and from Bolshevik propaganda." Ludendorff has recovered his nerve and wants to fight on. Then he and Hindenburg head back to Spa.

|

From

all his friends finally only Fuchsl, little fox, remains. The small white

terrier, apparently the mascot of English soldiers, had been chasing a rat in No

Man's Land. The dog had jumped into a German trench, where Adolf had catched him

- and kept him.

From

all his friends finally only Fuchsl, little fox, remains. The small white

terrier, apparently the mascot of English soldiers, had been chasing a rat in No

Man's Land. The dog had jumped into a German trench, where Adolf had catched him

- and kept him. That's why the

regiment of the quite fresh soldier Erich Paul Remark is send to that region

too. Adolf and Erich don't know each other then, but they serve close together.

There are only a few miles between Remark's 15th Regiment of the 2nd Guard

Reserve Division and Hitler's 16th Regiment of the 10th Bavarian Division.

That's why the

regiment of the quite fresh soldier Erich Paul Remark is send to that region

too. Adolf and Erich don't know each other then, but they serve close together.

There are only a few miles between Remark's 15th Regiment of the 2nd Guard

Reserve Division and Hitler's 16th Regiment of the 10th Bavarian Division. On

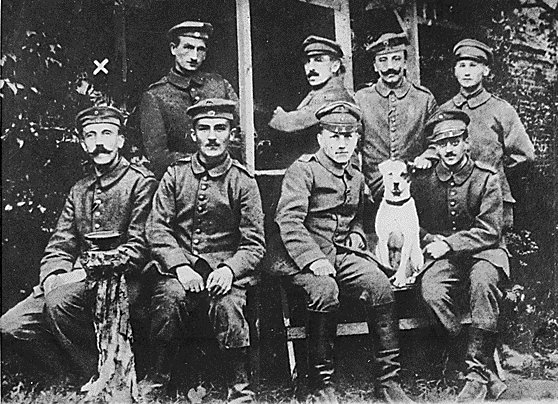

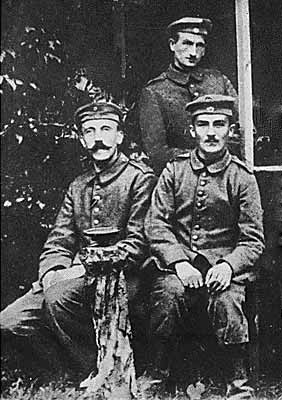

the Ypres front Adolf (picture right, with the big moustache) is still

doing his utmost best. One of his fellow soldiers later told that Hitler in this

period became less and less liked: "He was always deadly serious. He never

laughed, he never made jokes".

On

the Ypres front Adolf (picture right, with the big moustache) is still

doing his utmost best. One of his fellow soldiers later told that Hitler in this

period became less and less liked: "He was always deadly serious. He never

laughed, he never made jokes". For Erich Remark

the war is over too. One week after he was declared fit for service, the war

finishes. And then something peculiar happens. When the discharged soldier

Remark returns to his parental home, to Osnabrück, he suddenly wears a lieutenants-uniform.

On his breast he sports the Iron Crosses First and Second Class.

For Erich Remark

the war is over too. One week after he was declared fit for service, the war

finishes. And then something peculiar happens. When the discharged soldier

Remark returns to his parental home, to Osnabrück, he suddenly wears a lieutenants-uniform.

On his breast he sports the Iron Crosses First and Second Class. Adolf

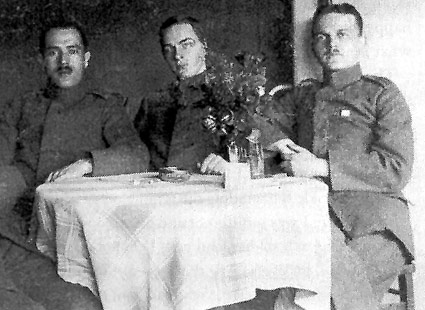

Hitler (see picture on the right) too publishes a book wherein he tells

about his war-experiences: Mein Kampf it is called and anyone who reads

the two books together fails to see that both are writing about the same war,

the same No Man's Land, the same trenches, the same soldiers, the same suffering

and death.

Adolf

Hitler (see picture on the right) too publishes a book wherein he tells

about his war-experiences: Mein Kampf it is called and anyone who reads

the two books together fails to see that both are writing about the same war,

the same No Man's Land, the same trenches, the same soldiers, the same suffering

and death. Events like this

did not fit in Hitlers book and in his way of thinking. Im Westen nichts

Neues too did not fit in - and the writer of that book not at all. In 1933,

the moment that Germany elects Hitler to power, he opens the hunt for Remarque.

In Hitlers eyes his former fellow-soldier has betrayed the Fatherland.

Events like this

did not fit in Hitlers book and in his way of thinking. Im Westen nichts

Neues too did not fit in - and the writer of that book not at all. In 1933,

the moment that Germany elects Hitler to power, he opens the hunt for Remarque.

In Hitlers eyes his former fellow-soldier has betrayed the Fatherland.